Interactive Web Report | AFTER THE PAUSE: The rise of eviction filings post-pandemic

The Web version of the report presented here is condensed from the downloadable PDF version of the report.

MAIN FINDINGS

This report is an evaluation of how eviction filings and filing rates have changed over time and the communities where changes are concentrated. It analyzes the eviction filing data captured by the Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts over a five-year span starting July 1, 2018, to June 30, 2023.

- Pennsylvania’s eviction filings and rates have returned to pre-pandemic levels after being cut in half during the pandemic due to robust tenant protections and financial assistance programs.

- 115,000 households over the course of the year or 310 renter households every day face an eviction filing.

- 87% of eviction filings are concentrated in 20 counties in Pennsylvania. 80% renter households in Pennsylvania live in these same counties.

- 16 of those 20 counties have filing rates above the statewide average.

- The zip codes with the highest concentrations of eviction filings are the same compared to the pre-pandemic time period.

- While judgments for the plaintiff (the landlord) remain the most common outcome of a court ruling, there has been a modest decrease. And cases withdrawn have seen a nearly equal increase when compared to pre-pandemic years.

- Over 90% of cases involve past due rent demonstrating that non-payment of rent continues to be a main driver for eviction filings and resulting evictions.

- The number of tenants involved in eviction cases are behind on rent by more than 3 months – an increase from 26% pre-pandemic to 31%.

- Two thirds of judgments for the plaintiff (the landlord) provide an opportunity for tenants to pay back rent (called “pay and stay”) up until the legal lockout to avoid eviction.

- More cases are continued now compared to pre-pandemic numbers, although not at the same rate at which cases were continued during the pandemic.

PREFACE

With the expiration of eviction moratoria and now the wind-down of Emergency Rental Assistance (ERAP) funding, Pennsylvania is witnessing a resurgence in eviction filings, approaching pre-pandemic levels. The state is home to nearly 1.59 million renter households, with 30% grappling with the burden of high rental costs, particularly low-income households. 69% of the 430,703 extremely low-income renter households are severely cost burdened.

An eviction, encompassing both formal legal processes and informal removals, represents the termination of a tenant’s right to live in the unit they are currently renting, typically initiated by a landlord, property owner, or property manager. The harmful impact of evictions extends across a spectrum of legal, economic, and social factors, affecting families, businesses, schools, and communities.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Pennsylvania, like many states, grappled with a significant volume of eviction filings. From July 2018 to June 2019, Pennsylvania recorded over 115,000 eviction cases, averaging about 315 filings per day across the state.

Notably, areas with higher populations of renters of color experience disproportionately higher filing rates, underscoring the impact of evictions on vulnerable communities. These disparities shed light on the unequal burden borne by marginalized populations in the face of eviction crises.

As the pandemic took hold, the government responded with the CARES Act and the state moratorium, followed by the nationwide CDC moratorium. These moratoria played a pivotal role in averting a homelessness crisis during the pandemic.

By temporarily suspending eviction proceedings for eligible tenants, these measures offered a vital safeguard, enabling people to remain in their homes while waiting to access pandemic related resources like ERAP and Pandemic Unemployment benefits. During this period, eviction filings in Pennsylvania plummeted to less than half of their pre-pandemic levels.

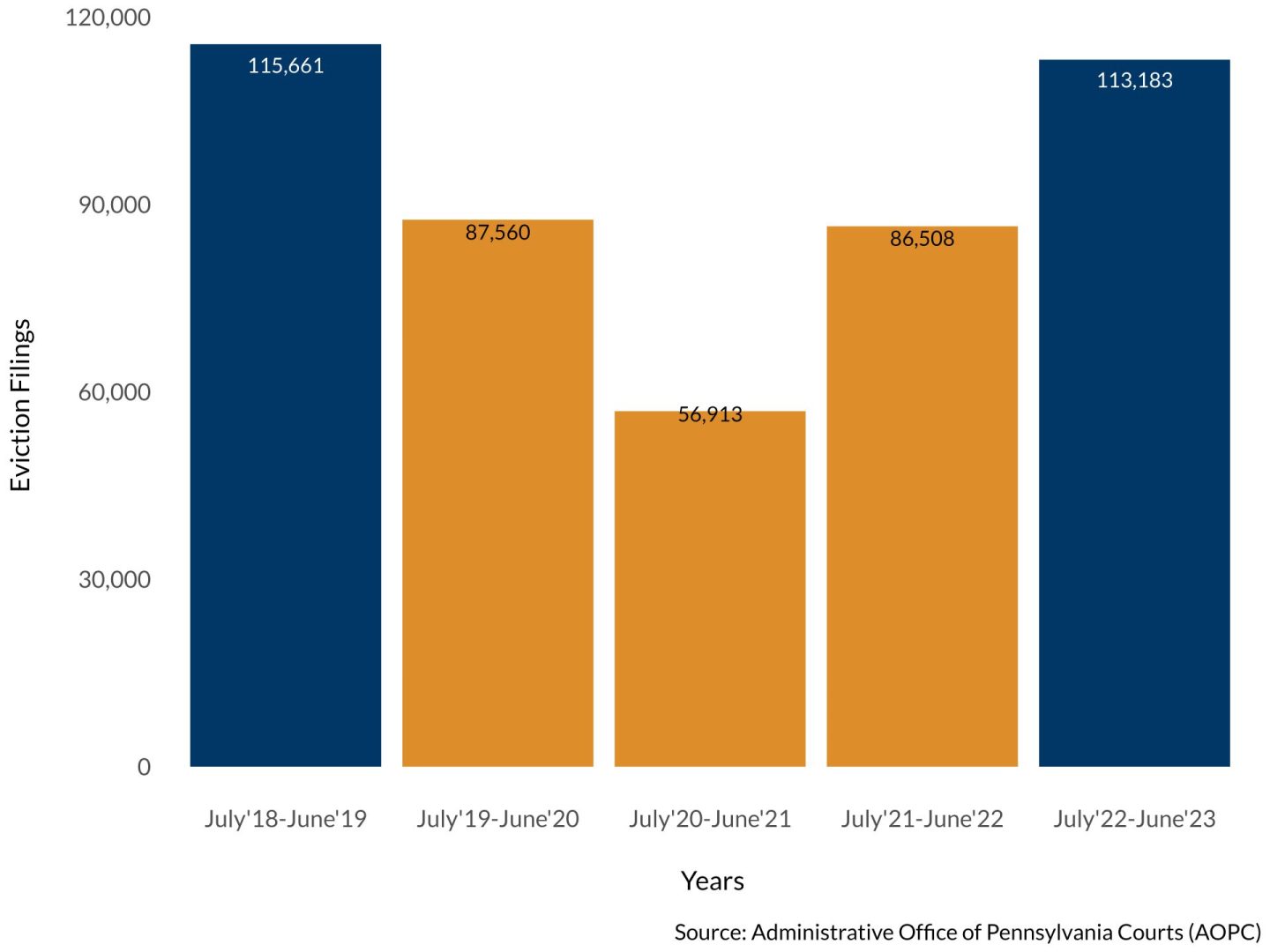

Statewide eviction filings have nearly reached pre-pandemic levels

Before the pandemic, from July 2018 to June 2019, Pennsylvania recorded approximately 115,661 eviction filings. As the pandemic took hold and eviction moratoria were enacted, the number of filings witnessed a substantial decline. The lowest point was recorded between July 2020 and June 2021, totaling 56,913, largely attributed to the implementation of the CDC moratorium.

However, since the end of nationwide relief efforts, eviction filings have steadily risen, with a notable spike in late 2021. In the period from July 2022 to June 2023, PA recorded 113,183 eviction filings, nearly 98% of the pre-pandemic filing level. To put it in perspective, this implies that approximately 310 renter households face eviction filings daily in the state.

The 3rd quarter of each year records the highest number of filings (excluding the pandemic)

The graph below highlights a recurring trend where a significant portion of eviction filings take place during the third quarter of each year. In 2019, the third quarter recorded the highest number of eviction filings at 32,445. Similarly, last year saw a peak in the third quarter, with 30,826 filings—indicating a potential seasonal pattern in eviction activity.Statewide Filings by Quarter

Note: you can hover your cursor over the graph to view the number of cases for each quarter. You can choose specific counties from the dropdown menu below. Individual county plots are available for download using the ‘Download Plot’ button.

Countywide Filings by Quarter

Statewide eviction filing rates are nearly at pre-pandemic levels

EVICTION FILING RATE: The eviction filing rate is a crucial metric used to gauge the frequency or incidence of eviction filings within a specific geographic area over a defined period, typically expressed as a percentage or as a rate per 100 households. Specifically, it reflects the proportion of rental households within that area that have had eviction cases initiated against them during the specified time frame.

In PA, the eviction filing rate followed a distinct trajectory. Before the pandemic, it was 7.3%, meaning that approximately 7.3 out of every 100 rental households faced eviction filings. This year, PA’s eviction filing rate has returned to pre-pandemic levels, now at 7.1%. In Pennsylvania, 1 in every 14 renter households faces the risk of experiencing an eviction filing.

87% of statewide filings are concentrated in 20 counties

Eviction Filings (July’22-June’23)

Note: you can hover your cursor over the map to view the number of cases and renter households for each county.

-

While statewide eviction filings in Pennsylvania are at pre-pandemic levels, there exist significant variations in both the number of filings and filing rates across counties. Notably,87% of all statewide eviction filings are concentrated in just 20 counties, as illustrated below. This concentration aligns with the fact that these 20 counties also host a substantial number of renter households (80%) within the state.

Eviction Filings in the top 20 Counties

Eviction filing rates by county

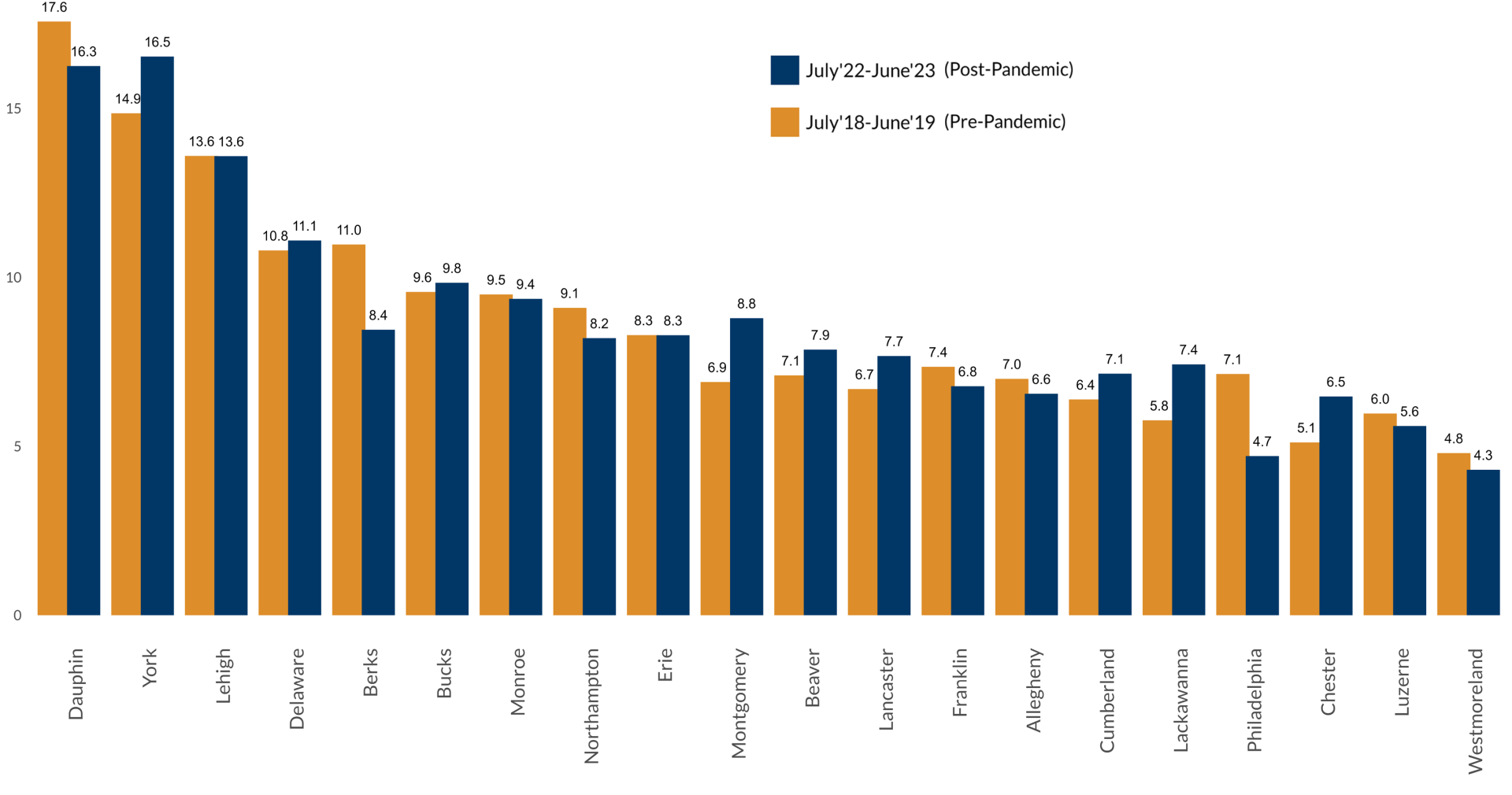

However, when we shift our focus to filing rates, a different narrative emerges. Counties such as Philadelphia and Allegheny, which have both the highest numbers of filings and the largest renter populations in the state, exhibit lower filing rates compared to counties with fewer renter households.

Examining filing rates helps us understand the severity of eviction challenges within a specific area because it takes into account the number of renter households. Philadelphia, Allegheny, Berks, Dauphin, Westmoreland, and others have experienced decreases in both the number of filings and filing rates over time. On the contrary, counties like Montgomery, Chester, York, Lancaster, and Delaware have witnessed increases in both filing numbers and rates.

Figure 4: Eviction Filing Rates (July’22-June’23)

16 of the top 20 counties with the highest filings exceed the statewide average filing rate

The graph below illustrates that 16 out of the 20 counties with the highest filings, also report filing rates exceeding the state average of 7.1 for the past year. Notably, Philadelphia has experienced the most significant decrease, while Montgomery has observed the most substantial increase in filing rates.

At the ZIP code level

-

When examining filing rates at the neighborhood level using census designated ZCTAs, it becomes evident that changes in filing rates vary significantly across counties. The map below provides a classification of areas based on their filing rates between July 2022 and June 2023, spanning a 12-month period.

The regions marked in red and orange indicate filing rates that are approaching or surpassing the statewide average of 7.1%. Notably, these areas are populations centers where it is more likely to see concentration of vulnerable populations at risk of eviction.

Comparing Figure 6 and 7 reveals an interesting trend that ZIP codes with higher rates before the pandemic also tend to have higher rates at present. The areas marked in light and dark blue have relatively lower filing rates, below 3.3%, and have largely remained consistent before and after the pandemic.

Figure 6: Eviction Filing Rate between July’22-June’23

Figure 7: Eviction Filing Rate between July’18-June’19

While a majority of cases were decided in favor of the landlord, an increased number of cases were withdrawn

-

Withdrawals and Settlements are crucial outcomes to monitor because they indicate that the landlord and tenant have reached an agreement or resolution outside of the court process. These outcomes often lead to better results for both the tenant and the landlord.

A landlord can withdraw a complaint by submitting written notice to the court before the hearing, resulting in the case being marked as withdrawn on the docket. Similarly, parties can inform the court of a settlement before judgment entry, leading to the case being marked as settled on the docket, and any scheduled hearings being canceled.

After the initiation of an eviction case, a hearing is scheduled before a judge. Unless the case is withdrawn by the landlord or resolved through an agreement (i.e., settled between the landlord and tenant), the judge is tasked with rendering a decision. This decision can favor the plaintiff (typically the landlord), favor the defendant (typically the tenant), or result in the dismissal of the case without prejudice. A dismissal without prejudice means that the plaintiff or landlord retains the option to re-file the case at a later time, if needed.

As shown in the graph, judgments are overwhelmingly in favor of the plaintiff. However, this proportion has experienced a decline, dropping from 80% before the pandemic to 73% in the most recent year (July 2022 to June 2023). Concurrently, there has been a consistent uptick in the number of cases withdrawn since 2018, from 8% to 13%. In contrast, judgments for the defendant (the tenant) and cases settled have exhibited relatively stable patterns over time.

Eviction Case Outcomes (excluding Philadelphia)

MOST EVICTION CASES INVOLVE BACK RENT

Unpaid rent is either the sole or one of multiple reasons for a significant majority of eviction filings. In the graoh shown, rent in arrears, often referred to as back or past due rent, is a claim in 90% eviction filings.

While costs, filing fees, and server fees have maintained relatively stable figures over the years, attorney fees have nearly doubled in the past year compared to pre-pandemic levels. Judgment amounts vary significantly across the state. The additional fees and charges included in the judgment award can be significant and increase the debt on the tenant by as much as 21%.

Judgment Award Categories (excluding Philadelphia)

66% of Judgments for Plaintiff provide a small window for tenants to pay back rent and avoid eviction

A grant of possession, , with minor exceptions, is included as part of the judgment that returns possession of the property (i.e. rental unit) to the landlord, terminating the rights of the tenant to continue to live there. Only if a landlord is awarded possession of the property can they initiate the next step in the legal process, which is filing the order of possession. This will start the 14 day countdown to when the legal lockout takes place and tenants are forcibly removed from the property.-

In 66% of cases where a judge has rendered a decision in favor of the plaintiff, most commonly the landlord, the tenant has an opportunity to pay the full judgment amount up until the moment of legal lockout, often called a “pay and stay.” In te figure below, the number of cases in which possession was granted, either with or without conditions, has remained relatively stable over time, with fluctuations observed during the pandemic.

The majority of orders of possession are issued approximately a month after a case is filed. Technically a landlord has up to 120 days to file the order of possession, though typically most happen immediately. In the past year (July 2022 to June 2023), the median time between filing and the issuance of an order of possession was 38 days, compared to 35 days before the pandemic.

MORE CASES ARE RECEIVING CONTINUANCES

-

A case continuance serves as a brief pause in the legal process, affording both parties additional time to address their specific issues or work towards a potential resolution.

In the period from July 2022 to June 2023, a higher percentage of cases, nearly 23%, were continued compared to 16% in the period before the pandemic. Notably, during the pandemic, nearly 33% of cases were subject to continuances .

CONCLUSIONS

Pennsylvania is home to over 1.5 million renter households and a third are struggling with rent cost burden. This rent burden can lead to untenable situations, especially for the 297,185 extremely low-income renter households that are severely cost burdened. Many renters are forgoing basic necessities like food or medicine to make the rent. During the pandemic, the robust financial assistance programs and tenant protections afforded to struggling families cut the eviction crisis in half. Unfortunately, as those resources and protections dry up, there is a return to pre-pandemic filing rates.

The harmful impact of eviction ripples through communities affecting families, landlords, businesses, schools, and communities. Eviction and efforts to prevent it are essential to ongoing efforts to achieve housing equity and justice in Pennsylvania.

The Housing Alliance is going to continue to evaluate the root causes of evictions, where they are taking place, and who is at risk. We are also going to continue to evaluate the community-based programs that divert and prevent evictions to capture the impact both within court data and throughout the broader community. Our commitment is to continue to work with communities to implement and expand programs to divert and prevent evictions and capture the collective benefit we all receive when all Pennsylvanians are stable in their homes.

rEFERENCES

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. “Report to Congress on the Feasibility of Creating a National Evictions Database.” 2021. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Eviction-Database-FeasibilityReport-to-Congress-2021.pdf

Allegheny County Department of Human Services. “How an Eviction Case Proceeds Through Allegheny Courts.” September 2020, p. 2. https://www.alleghenycountyanalytics.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/20-ACDHS-19-EvictionSupport_v4.pdf

Eviction Lab, “Eviction Map and Data (Version 2.0)” accessed November 1, 2023, https://evictionlab.org/map.

NLIHC, “Housing Needs by State: Pennsylvania” accessed November 12, 2023, https://nlihc.org/housing-needs-by-state/pennsylvania

U.S. Census Bureau, “ZIP Code Tabulation Areas (ZCTAs),” accessed November 13, 2023, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/zctas.html.KEY TERMS

In an eviction case, the defendant is the party who is being accused of violating the terms of the lease agreement. The defendant is usually the tenant who is facing eviction.

Disposition

The court’s determination of a case. Case dispositions (also referred to as “Case Outcomes”) include Judgment for Plaintiff, Judgment for Defendant, Settled, Withdrawn and Dismissed Without Prejudice.

Eviction

“[P]rocesses and means by which landlords remove tenants from their rental properties.” The term ‘eviction’ can also refer to the end state of the eviction process where a tenant is physically displaced from the property. Here, we distinguish between eviction filings, the eviction process, and the actual physical displacement. A legal eviction in Pennsylvania can only take place after a judge has issued an order for possession.

Eviction Filing

A landlord-tenant complaint where the landlord (plaintiff) sues the tenant (defendant) for recovery of possession of real property, including (if applicable) the payment of unpaid rent and damages. It is filed in the Magisterial District Court covering the location of the property (in jurisdictions outside of Philadelphia) or in Municipal Court (in Philadelphia).

Eviction Filing Rate

The eviction filing rate is a metric used to gauge the frequency or incidence of eviction filings within a specific geographic area over a defined period, typically expressed as a percentage or as a rate per 100 households. Specifically, it reflects the proportion of rental households within that area that have had eviction cases initiated against them during the specified time frame.

Grants of Possession

A legal order issued by a court that authorizes a landlord to take possession of a rental property from a tenant. This typically occurs after a legal proceeding, such as an eviction hearing, in which the court determines that the landlord has the right to regain possession of the property.

Judgment

The decision made by the judge hearing the eviction case. If the judge determines that the landlord’s complaint has been proven, the judge enters judgment for the plaintiff (landlord). The judgment may include monetary amounts for which the tenant is responsible to pay including rent in arrears, court costs, or other costs, as applicable. It may also include grants of possession or grants of possession with condition.

Notice to Quit

A written notice given by the landlord to the tenant specifying the date by which the tenant must correct a breach of the lease or move out. The notice to quit may provide a period of 10 or 30 days, depending on the nature of the breach (as stipulated in the PA Landlord Tenant Act), before an eviction case can be filed. This provision of Pennsylvania landlord-tenant law can be waived in leases.

Plaintiff

In an eviction case, the plaintiff is the party who initiates the legal action, typically the landlord or property owner.

Rent in Arrears

The amount of back rent owed by the tenant to the landlord. In most cases that are decided for the landlord, the judge will specify an amount of rent in arrears owed to the landlord.V

METHODOLOGY

The eviction data presented in this report was sourced from the Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts (AOPC) for cases filed between June 2018 and June 2023. This dataset contains information available in publicly accessible docket sheets; such as the number of cases filed, the amounts of rent arrears awarded to landlords, judgment outcomes, and more. These data can be analyzed at the state, county, and ZIP Code Tabulation Area (ZCTA) levels.

To provide context and a broader perspective, data on renter households were also integrated into the analysis. This supplementary information was procured from the 5-year American Community Survey (ACS), with the most recent available dataset being from 2021.

To facilitate comparisons across different time periods, the dataset was structured into 12-month segments, encompassing periods before, during, and after the pandemic’s impact. The state-level case tracking system does not encompass Philadelphia’s eviction filings. In this regard, data specific to Philadelphia eviction filings were drawn from Eviction Lab’s publicly available data, accessible via their website, as well as data obtained from the Legal Services Corporation. The Philadelphia dataset may lack some of the fields available in the AOPC data; therefore, many of our analyses do not include Philadelphia cases. These analyses are noted as such.

DATA LIMITATIONS

The data that was analyzed only included the information available on case docket sheets, which are electronically stored by the state courts system. The following are some limitations of these data:

Only cases that are formally filed with the courts are included within the dataset. Instances where tenants leave at the threat of eviction, are forced out, or are illegally locked out of their homes are not captured.

Pennsylvania law provides for a notice period (notice to quit) to tenants that infers a “right to cure” the breach of lease before a landlord can file for eviction. Pennsylvania law allows this provision to be waived, and it is commonly waived in private market leases. The consequence of the waiver is it denies tenants time in which to correct the breach to the lease before an eviction filing. To our knowledge, no dataset is available regarding how many notices to quit are given in Pennsylvania.

There are no readily accessible records of whether a legally sanctioned lockout is carried out. Once an order of possession is served, we do not know if a formal eviction was completed. Other possible scenarios include the tenant leaving (or being forced out) before the formal eviction, the tenant paying the arrears and still being evicted for minor breach of lease during period when landlord had right to file for order of possession, or the tenant paying their rent in arrears and staying.

There is no available data regarding tenant appearances, and as a result, we are unable to calculate the rate of no-shows. We do not know the reason(s) why an eviction complaint was filed. The state system does not provide this information electronically (or publicly). Though most eviction cases involve rent in arrears, we do not know if there were other reasons for the eviction filing.

Due to the structure of the state courts’ information management system as well as structural differences between local courts in Philadelphia versus the rest of the Commonwealth, we did not have case level data for Philadelphia eviction filings. We do not know which eviction cases were appealed.

The quantitative data we have do not account for the experiences and

circumstances of individual tenants and landlords. Our analysis was limited to publicly available data in bulk and does not include the qualitative context or other aspects of the eviction process not captured in the case docket sheets.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The views expressed herein are those of the Housing Alliance of Pennsylvania and do not reflect the views or opinions of those organizations listed in the acknowledgements.